The anatomy of a phishing attack

MitID (Danish eID) has become a relatively easy target for SMS phishing attacks. We take a look at how such an attack is put together and suggest ways to effectively end phishing altogether. One powerful remedy is to adopt new OS and browser credentials such as the FIDO Alliance passkey.

A phishing attack is when a hacker lures you into submitting sensitive information (e.g. login credentials) by posing as a legitimate party like your bank or teleoperator. But in reality, the site you visit is just the hacker's front for collecting your details. After collecting this data, the hacker can use it for their own gain, such as to steal money or take over your phone number.

With the widespread use of so-called eIDs—digital identities tied to you as a legal person—in the EU, many are subjected to phishing attacks. These attacks trick people into handing over their eID credentials, which are often the keys to financial and government services.

Let’s look at how such an attack may play out against the Danish MitID*. The hypothetical attack can also be seen in this recording of a live "hacking" session hosted by our partner, Liga.

*Similar approaches can be used with other eIDs, such as the Swedish or Norwegian BankID or Belgian itsme®.

1. The setup

First, the hacker prepares a fake copy of a well-known site, such as your bank. The site is wired to the hacker's phishing admin panel which will alert the hacker when a victim steps into the trap and enters their credentials into the fake website.

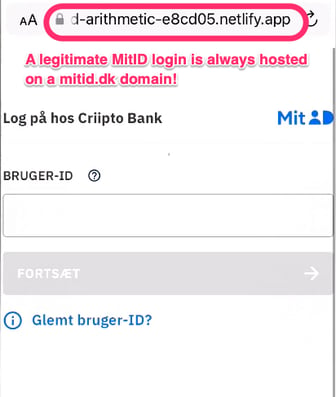

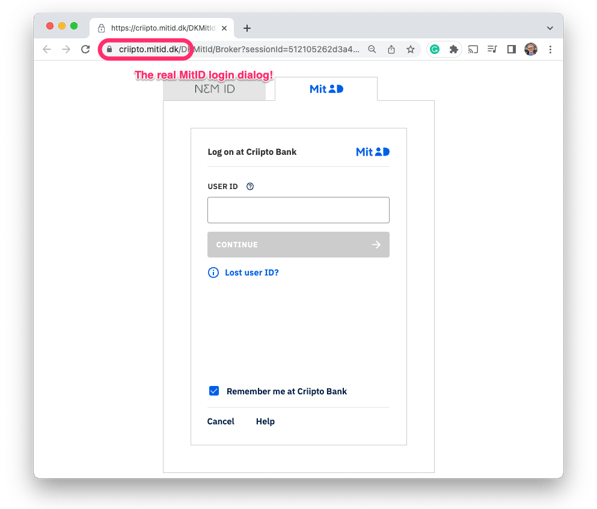

For MitID, the site will look like the real thing, except the URL will be off. An authentic MitID login box will always be hosted on a mitid.dk domain. So the success of a phishing attack depends on the user overlooking this vital detail.

2. The phishing hook is engaged

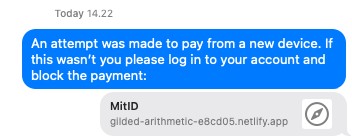

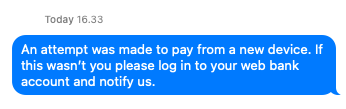

Once the fake site is set up, the hacker casts the net. This will typically be an email or an SMS text message (SMS phishing is sometimes called "smishing").

The hacker will typically send thousands of these messages to a huge batch of phone numbers acquired before the attack.

3. The victim is hooked

Out of the thousands of recipients, there will be a few who find the message plausible. This is similar to how an ad is shown to thousands of people to reach a smaller group that finds it relevant.

In the case of this specific SMS message, the victim may be a person who just started using a new iPhone or recently registered a new credit card in their Apple Wallet. They’re therefore more likely to find the message relevant and click the link without noticing the bogus URL. The victim might also simply be unaware of the significance of a URL and never see it in the first place.

The victim clicks the link…and the attack is now underway!

4. The successful capture of credentials

Clicking the link opens up the victim’s phone browser with the hacker'’s fake website. Unfortunately, the victim still doesn’t see the bad URL.

Remember: A real MitID login dialogue will always use a mitid.dk subdomain! Our unsuspecting victim now enters their credentials and proceeds to the next screen.

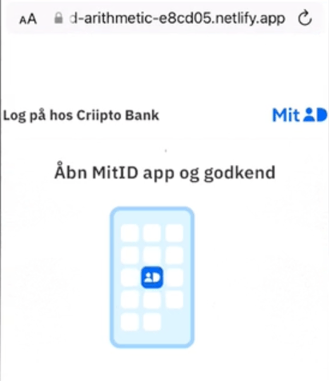

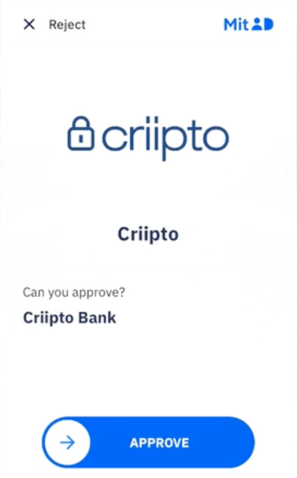

In the case of the Danish MitID, the screen now tells the user to open the MitID app on their phone to approve the login. The victim finds the MitID app and opens it.

Meanwhile, the hacker is alerted of the activity!

5. The hacker completes the actual break-in

The hacker gets ready to retrieve the login credentials as they are being entered.

In our MitID scenario, the hacker quickly picks up the MitID username typed in by the victim and enters it into the real banking website.

Once the hacker inputs the details, the app on the victim's phone displays an actual request to approve the login. Since this is precisely what the victim expects, they happily approve the authentication request.

The hacker now has full access to the victim's web bank. They’re now free to inspect it and try to transfer money out to so-called “mules” typically engaged in an actual break-in.

Note: Danish banks typically require an additional swipe in the victim's MitID app to complete a transfer. This means the hacker will need to successfully perform one more phishing operation against the same victim.

How could the victim have avoided this?

So how can the average person with Danish MitID defend themselves against these types of phishing scams?

For one, banks and government institutions must frequently remind the users about two crucial aspects:

- Banks and government entities never send out links by email or SMS. They simply ask you to log into your web bank, government site, etc. They never, ever supply the link!

- When you enter your credentials, always make sure you are doing so on a mitid.dk subdomain. This is because MitID cannot run on any other domain.

Also, if you ever fall victim to this kind of attack, call your bank as soon as you realize something is wrong! They can then prevent the attacker from doing the same to others.

How may we block phishing in the future?

People are increasingly aware of phishing attacks and ways to recognize them. But as long as the underlying approach and technology remain intact, we will continue to see successful phishing campaigns.

Luckily, there are at least two new technical capabilities that may help to reduce or eliminate phishing campaigns altogether:

Short-range radio

-

Relying on short-range radio wave connections—such as NFC or Bluetooth—between devices may eliminate the type of long-distance phishing that we described above. Today, the most common medium for binding devices together is a QR code. Hacking this process requires more advanced tricks, but it is certainly possible. With NFC or similar, this will no longer be the case!

Passkeys

-

Introducing site-specific, discoverable passkeys leaves nothing to phish. We must completely eliminate usernames and passwords from the authentication process. One readily available solution is the concept of passkeys as standardized by the FIDO Alliance with broad industry and platform support.

Passkeys have two fundamental qualities that eliminate phishing:

- The personal, cryptographic kets are tied to specific websites and cannot be used anywhere else.

-

They require no usernames or other ID, as they are automatically discoverable.

What's next?

For now, phishing is here to stay.

But initiatives are in the works that should completely eliminate it.

These technologies—most notably QR codes for device coupling and passkey for eliminating usernames and passwords—are already making their way into products and services. Norwegian BankID, for example, already supports passkeys for user authentication, and Swedish BankID has been using QR codes for a while.

Here at Criipto, we’ve already introduced our own generic, cross-eID QR option for channel binding. We’re now working on a general passkey option as part of the lead-up to upcoming ID wallets on your personal devices.

If that sounds relevant to you, talk to an expert about the available options and their benefits or learn more about how to improve MitID.